When you first build a source generator, it feels almost magical. You write a bit of code, rebuild, and suddenly a new *.g.cs file appears in your project.

In the first post, we built that magic: an incremental source generator that finds an interface annotated with GenerateApiClientAttribute and emits a strongly typed HttpClient implementation for it.

In this post, I want to pull back the curtain. We will look at the incremental pipeline that powers IIncrementalGenerator, and we will do it through the same GenerateApiClientAttribute example you have already seen.

By the end, you should have a clear mental model of how the Roslyn engine:

- Takes immutable compiler state, such as syntax trees and semantic models.

- Pushes that state through a series of pure transformations.

- Tracks dependencies between inputs and outputs.

- Recomputes only what is necessary when you edit a single line.

All of this is what keeps IntelliSense snappy, even when your generator is doing quite a lot of work.

Incremental generator pipeline architecture

The key idea behind incremental generators is that you are not implementing a single Execute method. Instead, you are describing a dataflow pipeline.

At a high level, the pipeline for our API client generator looks like this.

Each box represents a stage in the pipeline. The Roslyn engine runs these stages incrementally, caching the results of each step so that subsequent compilations can reuse work instead of starting from scratch.

In code, you describe this pipeline in Initialize using the incremental APIs on IncrementalGeneratorInitializationContext.

using Microsoft.CodeAnalysis;

using Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp.Syntax;

namespace MyApiGenerator;

[Generator]

public sealed class ApiClientGenerator : IIncrementalGenerator

{

public void Initialize(IncrementalGeneratorInitializationContext context)

{

context.RegisterPostInitializationOutput(static ctx =>

{

ctx.AddEmbeddedAttributeDefinition();

ctx.AddSource("GenerateApiClientAttribute.g.cs", AttributeSourceCode);

});

var interfaceDeclarations = context.SyntaxProvider

.ForAttributeWithMetadataName(

"ApiClientGenerator.GenerateApiClientAttribute",

static (node, _) => node is InterfaceDeclarationSyntax,

static (syntaxContext, _) => TryGetTargetInterface(syntaxContext))

.Where(static iface => iface is not null)!;

// Additional pipeline steps will follow...

}

}This code does not generate anything yet. It declares the first stage of the pipeline: how to scan the syntax tree and find the interfaces we care about. From here, we will layer on more stages that transform data into more useful shapes until we finally emit C#.

Immutable inputs: snapshots of the compilation

The first building block of an incremental pipeline is the set of inputs you get from the compiler. These include:

- Syntax trees (

SyntaxTree,SyntaxNode,SyntaxToken). - Semantic models and symbols (

SemanticModel,INamedTypeSymbol). - The

Compilationitself. - Additional files and config options.

All of these structures are immutable. Once the compiler hands you a syntax tree or a compilation instance, it will never change.

Immutability sounds like a theoretical detail, but it is the reason the incremental engine can safely cache and share data. There is no danger that a stage in your pipeline mutates a node that some other stage still references.

You see that immutability in the incremental APIs. Every time you transform data, you get a new value provider instead of mutating the existing one.

public void Initialize(IncrementalGeneratorInitializationContext context)

{

var compilationProvider = context.CompilationProvider;

var assemblyNameProvider = compilationProvider

.Select(static (compilation, _) => compilation.AssemblyName ?? "Unknown");

context.RegisterSourceOutput(assemblyNameProvider, static (spc, assemblyName) =>

{

spc.AddSource("AssemblyInfoFromGenerator.g.cs",

$$"""

// Generated for {assemblyName}

""");

});

}compilationProvider always represents a snapshot of the compilation. When anything in the project changes, the engine creates a new snapshot, and a new value flows through the pipeline. Older snapshots remain valid for any cached intermediate results.

Pure transformations: describing work as functions

Incremental generators are built around a simple rule. Each pipeline stage is a pure function from input to output. Given the same input, a stage must always produce the same output, with no side effects.

In the API client generator, the first significant transformation is from InterfaceDeclarationSyntax to a richer model that captures everything we need to generate code.

internal sealed record ApiClientModel(

string Namespace,

string InterfaceName,

string ClassName,

string BaseUrl,

ImmutableArray<ApiMethodModel> Methods);

internal sealed record ApiMethodModel(

string Name,

string ReturnType,

string ParameterType,

string ParameterName);

private static ApiClientModel? TryCreateModel(

GeneratorSyntaxContext context,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var ifaceSyntax = (InterfaceDeclarationSyntax)context.Node;

var interfaceSymbol = context.SemanticModel

.GetDeclaredSymbol(ifaceSyntax, cancellationToken);

if (interfaceSymbol is null)

{

return null;

}

var generateAttr = interfaceSymbol

.GetAttributes()

.FirstOrDefault(a => a.AttributeClass?.Name == "GenerateApiClientAttribute");

if (generateAttr is null)

{

return null;

}

var baseUrl = generateAttr.ConstructorArguments[0].Value?.ToString()

?? "https://api.example.com";

var methods = interfaceSymbol.GetMembers()

.OfType<IMethodSymbol>()

.Where(m => m.Name.StartsWith("Get", StringComparison.Ordinal))

.Select(m => new ApiMethodModel(

Name: m.Name,

ReturnType: m.ReturnType is INamedTypeSymbol { TypeArguments.Length: 1 } task

? task.TypeArguments[0].ToDisplayString() : "object",

ParameterType: m.Parameters.FirstOrDefault()?.Type.ToDisplayString() ?? "void",

ParameterName: m.Parameters.FirstOrDefault()?.Name ?? "_"))

.ToImmutableArray();

var className = interfaceSymbol.Name.TrimStart('I') + "Client";

return new ApiClientModel(

Namespace: interfaceSymbol.ContainingNamespace.ToDisplayString(),

InterfaceName: interfaceSymbol.Name,

ClassName: className,

BaseUrl: baseUrl,

Methods: methods);

}

This method is pure. Given a particular interface declaration and semantic model, it either returns the same ApiClientModel or null. There are no global caches, no I/O, and no side effects.

That purity is what allows Roslyn to memoize results. If nothing about the interface symbol has changed, the engine can reuse the cached ApiClientModel instead of recomputing it.

Incremental updates: only recompute what changed

Now consider the developer experience. You are in the SampleApp, editing the IUserApi interface. You change this:

Task<User> GetUserByIdAsync(int id);to this:

Task<User> GetUserByEmailAsync(string email);What does the incremental pipeline actually do?

- The compiler reparses only the changed syntax tree.

- The

CreateSyntaxProviderpredicate runs again, but only on the nodes from the affected file. - For the

IUserApinode, the transform stage is invoked again to produce a newApiClientModel. - All other interfaces that matched the predicate in other files reuse their previously cached models.

- The

RegisterSourceOutputstage sees that only oneApiClientModelchanged, so it only regenerates the correspondingUserApiClient.g.cscontent.

The rest of the pipeline does not run again. No other generated files are touched.

You can picture this as a tree of cached values that is updated locally when something changes.

Only the nodes highlighted as changed need to be recomputed. This is the essence of an incremental pipeline.

Dependency tracking and precise invalidation

Under the hood, each transformation you add encodes dependency information. The engine knows which outputs depend on which inputs.

For example, when you write:

var models = interfaceDeclarations

.Select(static (context, ct) => TryCreateModel(context, ct))

.Where(static model => model is not null)!;

context.RegisterSourceOutput(models, static (spc, model) =>

{

EmitClient(spc, model);

});

The engine builds a dependency graph that can be summarized as:

- Each

ApiClientModeldepends on exactly oneInterfaceDeclarationSyntaxand its semantic model. - Each emitted file depends on exactly one

ApiClientModel.

If you later combine providers, that graph becomes richer. Consider an additional configuration file that lets you customise naming conventions for the generated clients.

var configText = context.AdditionalTextsProvider

.Where(static file => file.Path

.EndsWith("apiclient.config.json", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

.Select(static (file, ct) => file.GetText(ct)?.ToString())

.Where(static text => text is not null)!;

var modelsWithConfig = models.Combine(configText);

context.RegisterSourceOutput(modelsWithConfig, static (spc, pair) =>

{

var (model, configJson) = pair;

var options = ParseOptions(configJson);

EmitClient(spc, model, options);

});

Now each generated file depends on both:

- The interface where

GenerateApiClientAttributeis applied. - The content of

apiclient.config.json.

If you change only the config file, all clients are regenerated, but the expensive semantic analysis of each interface is reused. If you change only one interface, only that client is regenerated, with the existing config still applied.

This fine-grained invalidation is handled entirely by the framework. Your job is to express dependencies clearly using the incremental APIs.

Chained transformations in the API client generator

Let us put the pieces together and look at a more complete pipeline for the API client generator.

public void Initialize(IncrementalGeneratorInitializationContext context)

{

context.RegisterPostInitializationOutput(static ctx =>

{

ctx.AddEmbeddedAttributeDefinition();

ctx.AddSource("GenerateApiClientAttribute.g.cs", AttributeSourceCode);

});

var interfaceDeclarations = context.SyntaxProvider

.ForAttributeWithMetadataName(

"ApiClientGenerator.GenerateApiClientAttribute",

static (node, _) => node is InterfaceDeclarationSyntax,

static (syntaxContext, _) => TryGetTargetInterface(syntaxContext))

.Where(static iface => iface is not null)!;

var models = interfaceDeclarations

.Select(static (syntaxContext, ct) => TryCreateModel(syntaxContext, ct))

.Where(static model => model is not null)!;

context.RegisterSourceOutput(models, static (spc, model) =>

{

EmitClient(spc, model);

});

}

There are several distinct stages here.

- Post-initialization emits the attribute definition once.

- Syntax filter narrows the candidate nodes to interfaces with attributes using

ForAttributeWithMetadataNameorCreateSyntaxProvidermethods - Semantic transform verifies that the attribute is

GenerateApiClientAttributeand creates anApiClientModel. - Source output renders the final C# code.

Each stage feeds the next. Because the transformations are pure and the inputs are immutable, Roslyn can cache every intermediate result.

Selective emission: generate only when it matters

Sometimes you do not want to generate anything at all. For example, you might decide that an interface with no Get* methods should not produce a client.

Instead of handling this inside EmitClient, you can shape your pipeline so that those interfaces are filtered out earlier.

var models = interfaceDeclarations

.Select(static (syntaxContext, ct) => TryCreateModel(syntaxContext, ct))

.Where(static model => model is not null && model.Methods.Length > 0)!;

context.RegisterSourceOutput(models, static (spc, model) =>

{

EmitClient(spc, model);

});The source output step is now invoked only when there is something meaningful to emit.

Selective emission has two important benefits.

- Performance improves because the pipeline work stops earlier.

- The project stays clean because fewer files are generated.

You can take this further and have different pipelines for different categories of inputs, all feeding into their own RegisterSourceOutput stages.

Cross-file awareness: aggregating multiple interfaces

Incremental pipelines are not limited to a one-to-one mapping between input and output. You can also build aggregations where multiple inputs contribute to a single generated file.

A common pattern is a registry or mapper generated from many annotated types. For our API clients, imagine generating a single ApiClientRegistry.g.cs that exposes all generated clients in one place.

var allModels = models.Collect();

context.RegisterSourceOutput(allModels, static (spc, all) =>

{

if (all.IsDefaultOrEmpty)

{

return;

}

EmitRegistry(spc, all);

});Here, Collect turns many ApiClientModel values into a single ImmutableArray<ApiClientModel>. This creates a many-to-one dependency. If any single interface changes, the registry is regenerated. Other generated files that depend only on one model continue to benefit from more granular caching.

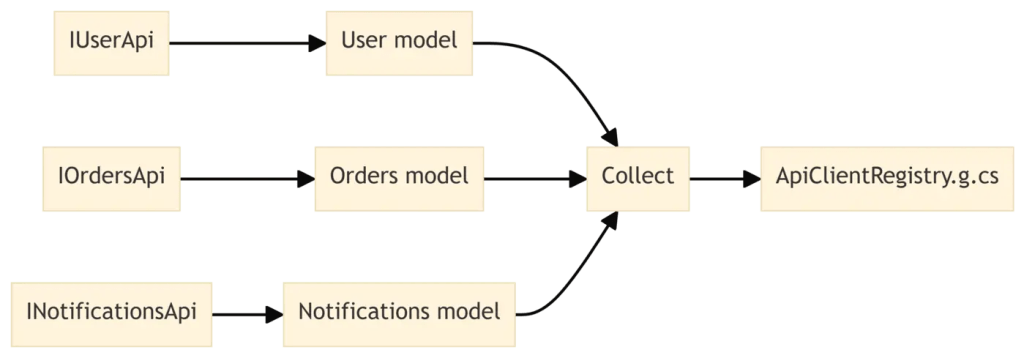

Visually, it looks like this.

This cross-file awareness is essential for scenarios such as:

- Generating one mapper for all DTOs.

- Emitting a single dependency injection registration method for many services.

- Building a consolidated OpenAPI description from multiple annotated endpoints.

Performance benefits in real projects

So far, we have focused on the shape of the pipeline. Let us talk about why this matters in real codebases.

Traditional, non-incremental generators implement ISourceGenerator and run their Execute method on every compilation. Even if almost nothing changes, the generator walks the entire syntax tree, recomputes all analyses, and regenerates all files.

Incremental generators avoid this waste through:

- Caching intermediate results per input.

- Selective execution based on dependency tracking.

- Immutable snapshots that are safe to share across threads.

The impact is most visible in the IDE. When you type in IUserApi, the syntax predicate runs very quickly. Only when you finish a valid interface declaration does the semantic transform run and update the generated client.

In large solutions, the difference is dramatic. Instead of spending hundreds of milliseconds or more in each keystroke to recompute generator output, the engine spends microseconds running predicates and only occasionally reruns the heavier stages.

You can inspect this behaviour using the generator diagnostics available through GeneratorDriver in your tests, or by enabling emission of compiler-generated files and watching when they change.

Practical guidelines for building incremental pipelines

When you design an incremental generator, the goal is not to be clever. The goal is to make dependencies and transformations explicit so that the engine can optimize on your behalf.

Here are some guidelines that emerge from the concepts we have covered.

- Keep inputs immutable and pure. Avoid static state, random values, or I/O inside your transformations.

- Do the cheapest work first. Use syntax predicates to filter candidates before you aggressively touch the semantic model.

- Shape data into small models. Transform syntax and symbols into records like

ApiClientModelthat are easy to reason about and test. - Use

Where,Select,Combine, andCollectto express dependencies. Let the framework handle invalidation; focus on correctness. - Filter early for selective emission. If an input does not need to produce code, keep it out of the final stages of the pipeline.

- Aggregate deliberately. Use

Collectonly when you truly need a global view, since it forces broader invalidation when any input changes.

If you follow these principles, you will get generators that feel “free” to your users, even on large codebases.

Rethinking generators as data pipelines

It is tempting to think of an incremental generator as a glorified string builder that runs during compilation. However, as you dig into the pipeline, a different picture emerges.

An IIncrementalGenerator is a small dataflow program inside the compiler. It consumes immutable snapshots of your code, applies a series of pure transformations, and emits new code only when the underlying data changes.

Once you see generators this way, new opportunities open up.

- You can confidently add richer analysis because you know it will be cached.

- You can model complex relationships such as cross-file aggregations.

- You can treat configuration files as first-class inputs instead of ad-hoc hacks.

In other words, you stop fighting the compiler and start collaborating with it.